Silence of the ad lambs: Google, Facebook's sprawling, covert influence and overt funding has strangled open industry debate in Australia

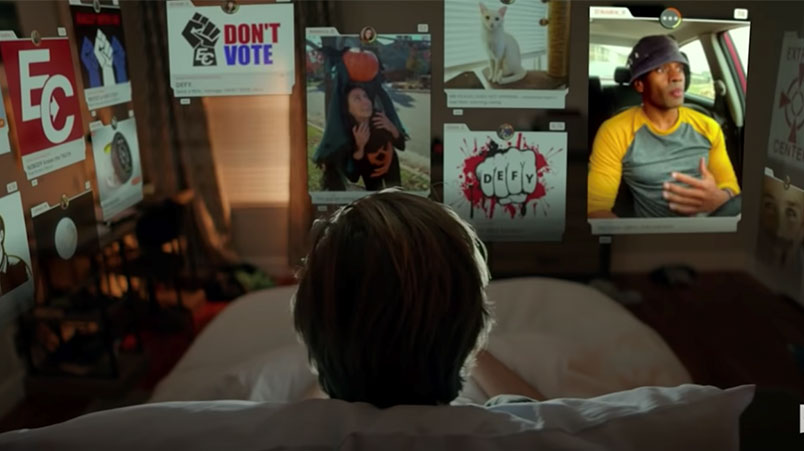

Netflix's The Social Dilemma (watch it at all costs). Advertisers must contain Big Tech, yet have almost entirely funded its growth.

The tech giants are either funding, are on the boards or are important to the revenues of most Australian advertising and marketing industry associations, big consulting firms, the market research industry, PR groups, global ad agency networks and an armada of independent, local agency entrepreneurs and advisors. Few will talk publicly on the current, bitter stoush between Big Tech, the ACCC, the Federal Government and Big Media, except for those disdainful of Big Media – News Corp particularly.

Netflix’s The Social Dilemma doco is disturbing

If you read nothing more of this, put 90 minutes in your diary now to watch the The Social Dilemma on Netflix, a confronting documentary-drama which last week was ranking in the global top five for the streaming service. It’s triggering much private conversation across Australian (and global) industry because it features Silicon Valley tech industry leaders who are now scared, literally, about the social, societal, competition and innovation consequences of the advertising-funded, attention arms race they helped weaponise for the 21st century. Book it in your diary. I’ll wait…

An op-ed a month in the making

On Monday 16 August, Google blew up on the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) and Federal government’s plans to strike a mandatory code in which it and Facebook would have to pay Australian media companies for the content they carry across their platforms.

The issue has splintered and muzzled the industry. It's a tough one because the ad-funded tech duopoly, with market valuations approaching a trillion dollars each – combined they are bigger than the Australian economy - are now central to the entire marketing, media and advertising supply chain here.

It’s been well-documented that Google, followed a few weeks later by Facebook, launched a public information campaign to mess with the public mind with claims its “free” services were "at risk" because of plans by the Feds to make them pay media companies for some stuff. Some of it very important stuff.

Public trust in Google or the Feds? No-one dares say

Beyond the immediate coverage Mi3 planned on market reactions to the brazen move by Google to take on the Feds and the ACCC, similar in intent to the mining sector's success in skewering former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd's resource super profit tax in 2010, I wanted a sense on which way public sentiment would fall on Google’s public lobbying effort. Would public trust in tech companies be greater than media or government and its institutions?

It hit home when I received a text from a tradie friend being hit from all angles with Google’s “Open Letter” to Australians. “Would love your thoughts on what’s happening with this shit,” he asked with a link to Google’s Open Letter. “Got this when I was about to search.”

In the following days, I approached numerous consumer research companies for their take. It was a brick wall of silence. From large quantitative research outfits we all know to smaller, local qualitative firms and even the market research industry’s peak body, no-one wanted to play.

They were either working for Google or the territory was too hot. The code was by speaking up they risked not ever being on Google’s payroll or just did not want to poke the bear. (Notable exceptions on this front were The Owl Insights’ Matt Sandwell and The Brand Institute’s Karl Treacher, both, with caveats, leaning to Google’s superior communications prowess and network reach to outplay government. And because the effort required by the Australian public to comprehend the complexity was too great, given other events like a pandemic).

The reticence from most of the research sector reminded me of a conversation with a partner at a Big Four consulting firm a few years ago over a theme I wanted to explore as the moderator for an industry conference panel – he agreed enthusiastically the topic was important but wouldn’t go there because Google was a client.

After failing spectacularly to glean an array of views from the research industry in the first week of Google’s August salvo, I went public on LinkedIn to enlist corporate communications and public affairs specialists. It was their sweet spot, I figured. They’d pile in with a view. Same story. Mostly silence.

Indeed, one industry exec told me last week that a public comment he made triggered a flurry of private messages from industry peers warning him of the risks of future work with Google because of his statement. More industry lambs had self-censored.

Which gets me to the peak industry associations.

I know many of the people in there – most are decent but are blinkered by the economics of survival. Some, in my view, are myopic on the consequences of the global duopoly and remain advocates – more on that later.

The duopoly and the industry dilemma

Very few are comfortable publicly engaging in a debate that might challenge the tech duopoly and here's the rub: Google is on the board of the Australian Association of National Advertisers (AANA). Facebook is on the board of the Association for Data-driven Marketing and Advertising (ADMA); Google and Facebook have partnerships with the Advertising Council (formerly the Communications Council) and Google and Facebook are on the board of the Interactive Advertising Board (IAB), which one board member told me means the peak digital advertising body is all but neutralised on taking a position regarding the ACCC’s proposed code. “We can’t touch these topics,” the board member told me. “They are issues the IAB can’t deal with. The IAB can’t have a position on this code.”

The Media Federation of Australia (MFA) doesn’t have direct board representation from Google or Facebook but, like much of industry, has used the boardrooms and events space at Facebook's lavish headquarters atop Sydney’s Barangaroo.

Many, understandably, use Facebook’s circa $4m state-of-the-art studios and entertainment facilities to save money they don’t have. There’s also the elite Facebook Client Council, which has some of Australia’s biggest brands, CMOs and agency groups around its table.

Agency groups of all types, meanwhile, strive for status as a Google “Preferred Partner” to showcase their digital and innovation prowess.

The point? Industry at large has collectively become reliant for survival on two Silicon Valley advertising giants pulling $4.6bn from the Australian advertising market with complex – and legal - international tax-avoiding structures. The reliance is simply a by-product of two companies being too dominant.

In a media context, it's why the Federal government and the ACCC are moving. There are protests aplenty about the policy being misguided and a sort of Government-Murdoch-Costello plan to prop up big, old media regimes; that a more independent and diverse media policy would be better served by some sort of digital tax that went into a collective pool to underwrite journalism. The French tried that last year. That really worked, right? It's still worth trying, but it seems to me that vocal parts of the industry would prefer to see Google and Facebook's profits and power protected over media companies because they are simply better. They are not.

The pressure Google and Facebook now have in the Australian market is sometimes explicit but not always.

Like the “anticipatory compliance” that former News Corp executive Bruce Dover wrote of in his book 12 years ago about how Rupert Murdoch influences his editors (met with strident disagreement from the company), much of the marketing and advertising industry is facing a similar challenge in their dealings with Google and Facebook. (Rupert's Adventures in China: How Murdoch Lost A Fortune And Found A Wife.)

The News Corp paradox

Which gets us to News Corp and Big Media in the current ACCC smash-up.

There are many in adland who are, paradoxically, aghast that the government’s street fight with Big Tech will benefit what they see as old, lumbering media institutions.

Certainly, more progressive types are horrified that what they see as the climate change-denying agenda from the Murdoch machine here and abroad will be funded by Australian government policy; that socially divisive editorial agendas will be propped-up and that both the strong-arm and covert tactics used to entrench or bring down political parties and leaders will continue.

These are valid arguments which should be – and are – debated. But they are paradoxical protests because Big Media critics fail to see the very same danger that is already here with Big Tech. Or simply won’t speak out. They are being played.

Again, watch The Social Dilemma on Netflix.

Somehow, the critics of Big Media and the current ACCC bargaining code have convinced themselves that editorial manipulation of the public by editors in the advertising-funded arms race to get consumer attention is less of an evil than human-less, AI-fuelled algorithms from Big Tech. To be clear, Facebook and Google are fracturing civics and politics, propelling an outrage culture, increasing teenage depression, self-harm and suicide and doing more, faster to consolidate global advertising monopolies and stifle innovation than any legacy media group has ever managed. We're in a classic boil-the-frog in water scenario.

No question Big Tech has brought about some impressive change and benefit. But to believe they are fundamentally better than the industries they are usurping is at best myopic and at worst, negligent.

No question, legacy media companies have been too slow, had too much swagger and arrogance and continue to engage in short-term, self-serving antics to smash direct competitors while failing to collectively tackle the tech barbarians at the gate.

But many of those legacy media characteristics are simply shifting to the new tech players with greater velocity and heavier consequences.

They are not better and, I think, more profoundly problematic.

I have plenty of reasons to turn on the sometimes brutal approach of News Corp and the past Machiavellian and petty politics of the former Fairfax Media regime. I’ve been royally shafted by both at various times in the past 20 years of my career on the mastheads.

But, for all the wayward media behaviour and conniving by even my journalist peers at times, what we face now from Big Tech is far more unsettling. For many, though, apparently, we are a better, smarter, more robust, diverse and innovative Australian industry for our new (global) monopolies.

We are being romanced by gigolos. This is not a sweeping slight on the individuals inside these organisations – although many are comfortably numb – but a challenge to the collective, the culture and the consequences of Big Tech.

What now for Australian media, adland and the tech bullies?

Enough of the philosophical indulgence. If you’re still here, well, thanks. Here comes the social media inspired fast sugar hits on where we are at:

- Until about 2018, industry "experts" scoffed at legacy media organisations over their bumbling attempts to innovate

- Plenty of it is true but here’s the thing – all the fast-moving digital pure-play publishers – Vice and Buzzfeed are the pin-ups for this set – have peaked and are now scrambling. Fit-for-purpose digital content engines were still not enough to compete with Google and Facebook

- The ad market did not reward innovation in content and distribution (social sharing and distribution, for example). Rather, the ad market rewarded Facebook and Google and their ever-changing algorithms and policies that hurt the smart, the fast, the slow and the slack in professional content creation

- Rupert Murdoch and News Corp, for all their transgressions, led the charge on behalf of global publishers to put up paywalls and implement digital subscription strategies to offset the collapse in advertising. They were widely ridiculed and scoffed in the early part. Murdoch had the balls. For those that think they understand the media business, don’t underestimate how deeply disruptive that was to the internals of publishing businesses that had stupidly, in retrospect, given away its online content for free 20 years ago

- Murdoch, News Corp and its CEO Robert Thomson led the global fight against Facebook and Google on content distribution. Dismiss the motives, sure, but to reiterate, no-one else stood up before them

- Critics of the ACCC's mandatory bargaining code say it’s a stitch-up by government looking after their big media mates at the expense of independents and diversity; that any dollars extracted out of Big Tech will go straight to Big Media’s bottomline with little re-investment in journalism; and in one instance, the money will simply head offshore to another tax-savvy US company – News Corp. Probably partly right. But... the advertising market has not supported small or diverse publishers for years. It wants scale, easy reach and now, privacy-bending user targeting – aka Facebook and Google

- There’s a strong argument by some independent publishers, about independent publishers, that they have been played by Big Tech in the lead-up to the ACCC’s mandatory bargaining code. Google handed out cash to players like Private Media (SmartCompany, Crikey) and Schwartz Media (The Saturday Paper, The Monthly, Quarterly Essay ) and then pulled when it was clear the Feds were not going to back down

- Independent publishers with revenues of $150k or greater will qualify for revenue sharing under the proposed mandatory code, the ACCC said last week

- The pool will probably be $200-300m, according to some industry estimates, not the $1bn flagged by News Corp or the $600m by Nine, if Facebook and/or Google don't pull from the Australian market

- Nine and News Corp will get a large proportion of the money - perhaps 50-60% but some independents are upbeat they will get material sums which will allow them to invest in their editorial products. Says one: "News media businesses only need to generate $150K in annual revenue to meet the revenue test in the draft code. That could be a one-person newspaper in regional Australia, so I don't accept that the code will only benefit the large players. On the contrary, the code provides the ongoing regulatory environment that would enable small publishers to fairly negotiate, which is not possible for many now."

- Those who have been working the lobbying circuit say policymakers were wavering a few weeks ago but have renewed their resolve; Labor and the Greens will back the government if the ABC and SBS are included in the mandatory code; some believe News Corp is against the move but this is unlikely

- There remains a decent possibility Facebook will pull local and international news from Australian feeds; this will hurt publishers like oOh-owned Junkee, Daily Mail and Broadsheet more acutely because they generate much higher referral traffic than others from Facebook

- The likelihood of Google pulling out from Australia is lower but still possible and far more disruptive to the local market than Facebook. Neither are used to being bossed around and neither want to set an international precedent for other markets. "Whether Facebook follows through on their threat to remove news is a matter for them, but that decision would penalise a large range of publishers - big and small - because they want to preserve their dominance of the digital advertising market," says one publisher. "It's important to remember that this is primarily a competition issue - the ACCC found that Google and Facebook are distorting the digital advertising market where they compete with news publishers by taking over 70% of all spend."

- Newsmedia subscription traffic from Google search, and to a lesser extent Facebook, will be a problem for newsmedia if Big Tech pulls. Some argue this is being underplayed by media groups

- More broadly, the ACCC is now working on its inquiry into adtech and media agencies; the marketing and advertising supply chain has not been under this level of regulatory scrutiny since 1996 when the old media accreditation system, co-designed by Rupert Murdoch 25 years earlier, was outlawed. The AANA was the catalyst for that change, arguing media companies had too much power and control

- Now advertisers have new beasts to contain in Big Tech, with far more complex challenges around competition and market power, but also unprecedented consequences for civics and democracy. Paradoxically, these tech companies are almost entirely underwritten by the advertising market

- Open industry debate is fundamental to making a sensible contribution

- Watch The Social Dilemma.