Next wave: Everything marketers need to know about the streaming-TV-online video shake-out; audience forecasts, advertising shifts, where next – Ampere Analysis

An Mi3 editorial series brought to you by

Mutinex

Ampere Analysis' Guy Bisson: Subscriber growth maxed out, so streamers are coming hard for ads. But the short-term impacts in Australia may be overcooked. If broadcasters can flip to streaming-first models, they can weather deeper long-term damage.

An Mi3 editorial series brought to you by

Mutinex

The wave of TV disruption from streamers has accelerated as they pile into ads amid flatlining subscriber growth. That means faster fragmentation of audiences and ad dollars as global platforms attack TV’s heartlands, focusing on crime and documentaries for older viewers and investing more in realty and non-scripted shows. Streamers bidding for sports rights pose sufficient threat for Disney, Fox and Warner Bros. Discovery to set aside rivalries and launch a joint platform. Ampere Analysis veteran analyst Guy Bisson thinks similar collaboration from broadcasters locally may be required – and could be good for audiences. Across the piste, Bisson breaks down where audiences are going, how much time they are spending on each channel, and where the money’s headed – with Australia ahead of the global tipping point on streaming versus TV consumption, but as yet behind in terms of TV-video ad dollar reallocation. Plus, how broadcasters can hold onto the lion's share of ad dollars and regain audiences – if they go all-in on streaming ahead of broadcast.

What you need to know:

- For broadcasters, the push by Amazon, Netflix and others into ads kills the old TV versus online video debate and removes their moat around ad-funded quality long form video.

- From a marketer perspective, says Ampere Analysis veteran analyst Guy Bisson, “It's no longer about ‘should I do TV, or should I do online?’ It's, ‘I can do everything I can do on TV on streaming’.”

- But it means greater fragmentation of audiences – tougher for advertisers to stitch together and tougher for publishers to fight for their share.

- Which is why broadcast networks are suddenly feeling major pressure.

- Meanwhile, the streamers have their eyes on TV’s heartland, making more documentaries and crime shows for older audiences, starting to push into non-scripted and reality shows to gain younger audiences for lower outlay, and bidding for sports rights – though Amazon’s Premier League experience suggests it’s not a guaranteed win.

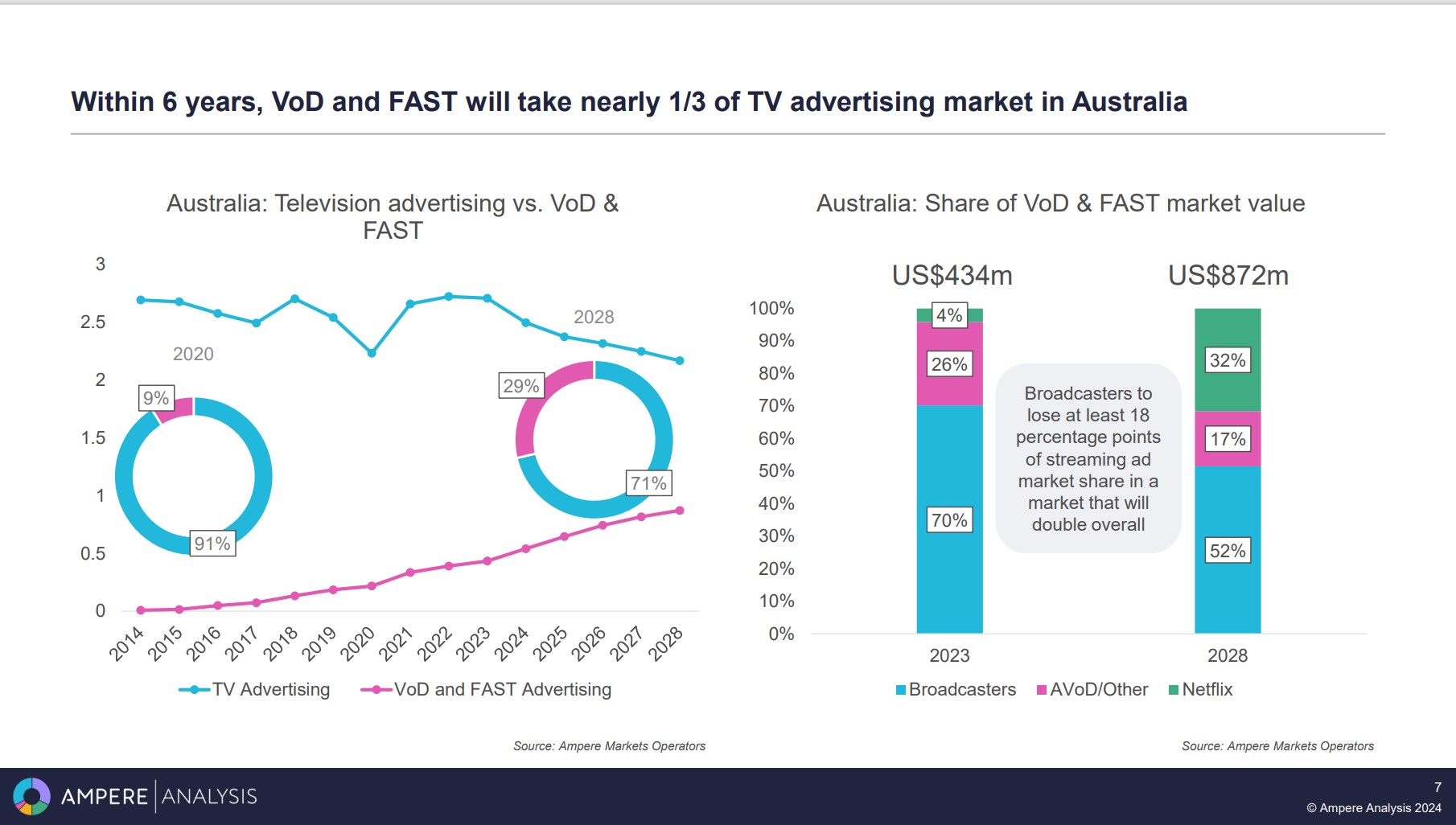

- Bisson says Australia’s broadcasters have managed to hold the line on ad share for now, despite audiences actually reaching a broadcast-streaming tipping point faster than other markets. And he predicts broadcast networks to still command the bulk of ad dollars in 2028. But streamers will be taking a much bigger share.

- He advises broadcasters to go streaming-first for more of their shows premieres. That way, they get more fresh first party data, more targeting capability and stand a better chance of winning back younger audiences now conditioned to streaming.

- Plus, they could do worse than look at big network collaborations in the US in the face of streamer incursions.

- Bisson thinks the immediate doomsday sentiment may be over-cooked locally, though he warns long-term the impacts could be deeper than anyone can yet reasonably forecast.

- There's always more in the podcast. Get the full download here.

[Global streaming platforms] have this double-pronged ability to do what TV does well, which is brand safe advertising across a large audience … and then they can do quite specific targeting. [For marketers] it's no longer about ‘should I do TV, or should I do online?’ It's, ‘I can do everything I can do on TV on streaming’. That’s a really interesting dynamic – and that is why everything has shifted in just this last eight to twelve months.

Follow the money

LA-based global TV and streaming analyst Guy Bisson has been tracking the industry for three decades. He says the disruption in TV and video in the past 12 to 18 months is unprecedented – with major impacts for marketers seeking audiences and business results via circa US$350bn in global ad dollars.

He breaks down where the money is currently flowing – and where it’s headed. But even that comes with major caveats – because streaming is moving so quickly and definitions are blurring.

Bisson defines TV as traditional linear broadcast television versus online video, which is basically social media. He groups video on demand streamers with FAST, or free ad supported TV.

“To put some numbers on that globally, online video [i.e. social] is the biggest segment at US$193 billion a year. Television is a little bit behind at US$128 billion. FAST, where Netflix and platforms like Tubi, Pluto and Freevee from Amazon sit, is about US$22 billion dollars at the moment, but growing quickly,” says Bisson.

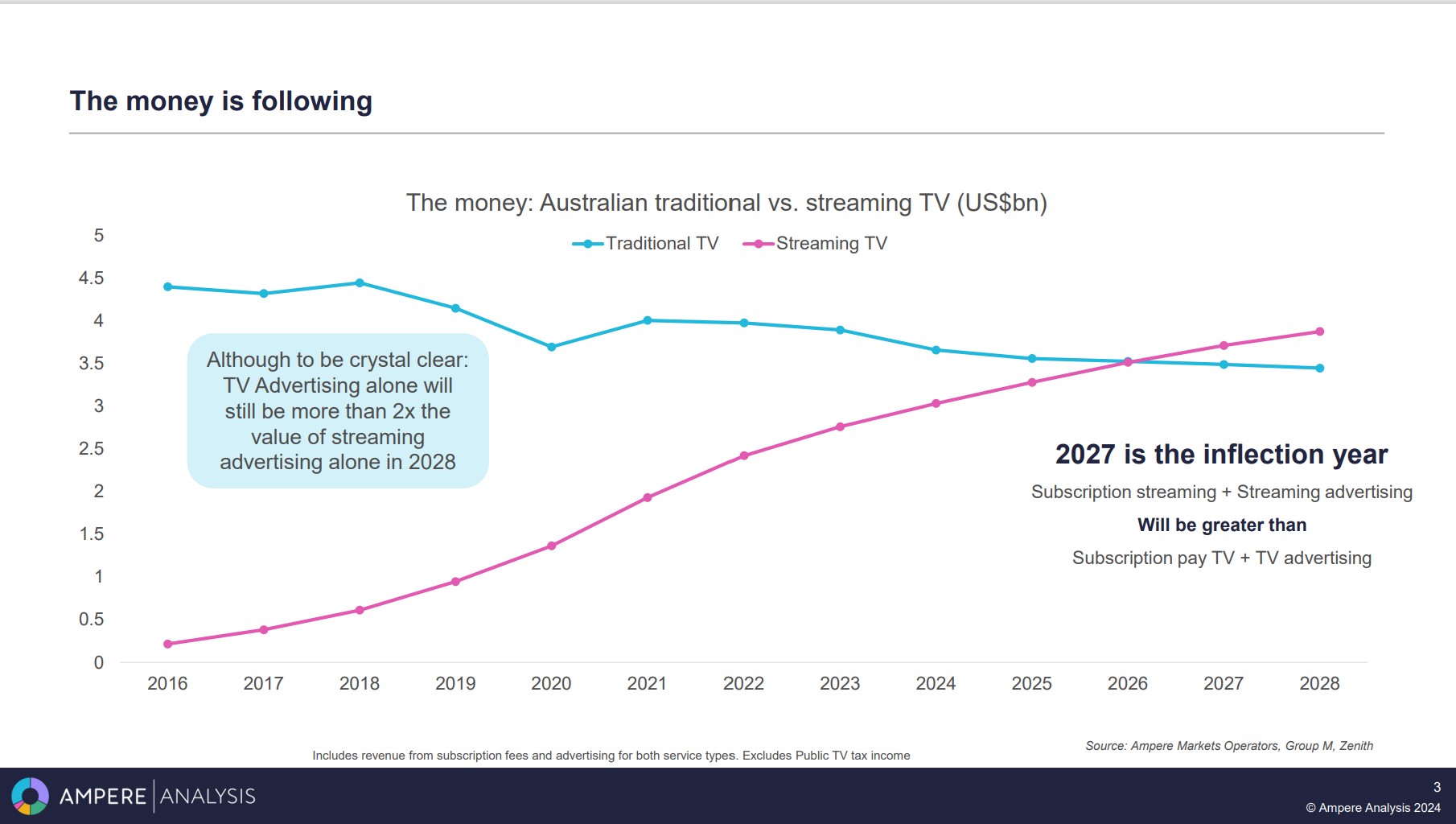

“To give some perspective on Australia, television is about US$2.5 billion (AU$3.83bn), online [video, specifically social] is similar at about US$2.5 billion in 2023 and that VOD segment is still quite small, at US$0.4 billion.” His figures tally broadly with Think TV’s numbers for 2023, which put total TV at AU$3.4bn, but don’t include Foxtel, SBS and Netflix ad takings.

By 2029, Ampere Analysis predicts the following global figures: “TV today is US$128bn. In six years time it will be US$132bn, so some small growth but broadly flat. By contrast, the online video segment, our social segment, will go from US$193 to US$280 billion, around 30 per cent growth,” says Bisson. “VOD and FAST, where Netflix and Amazon sit, will go from US$22bn to US$45bn, so slightly more than doubling. And that is almost certainly an underestimate. The nature of forecasting is that we don't know what we don't know. There will be launches that we haven't even considered or thought about yet during that six year period – because it's such a fast moving growth area.”

The upshot is an 18 percentage point share shift of the overall video ad dollar pie moving to streamers “that would conceivably have gone to the broadcasters”, says Bisson. “And again, that's probably an underestimate.”

Follow the eyeballs

Ampere has been surveying audiences across 29 countries for the last nine years. The figures, which are self-reported, “don’t quite align with audience measurement bodies” in those countries, but “do broadly align in terms of total daily viewing time”, per Bisson.

“Depending on market, there's somewhere between four and five hours a day that people spend watching television in some format,” he says. That includes all streamed content and social video “but the bulk of it is made up of long form-type television”.

Averaged across those 29 markets, “linear television and streamed television, so broadcast channels [versus] the likes of Netflix, are now roughly equal at one hour each day. By contrast, social video is about 40 minutes a day. Streaming from the broadcasters – which you could reasonably add back into their linear number of an hour – is another 31 minutes. And then we've got ad supported streaming – the FAST channels and the likes of Pluto, Tubi, Freevee from Amazon – is only about eight minutes at the moment,” says Bisson.

He compares that to Ampere’s 2017 viewing time survey data, where “linear TV was double what it is today”, while streaming “was half what it is today, so one has doubled and one has halved over that short period” with streaming getting a bigger boost than most during the pandemic.

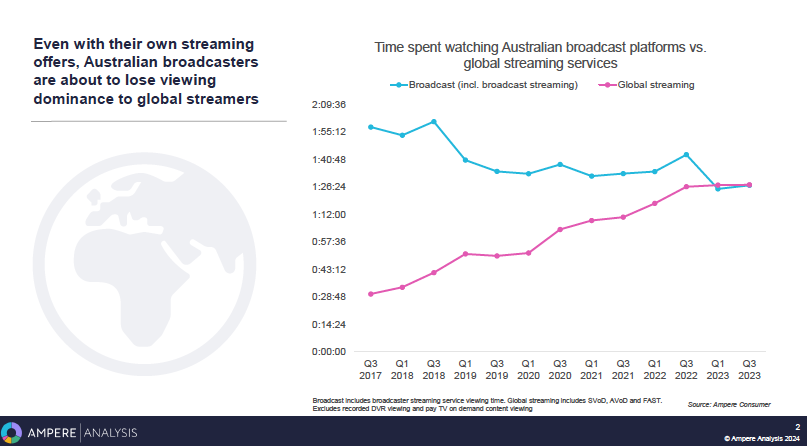

Bisson says viewing time per channel has shifted more rapidly in Australia. But notably, the money hasn’t. Yet.

“The big difference is that people here [in Australia] report that they watch more streamed content (more SVOD as we call it from Netflix and others) than they do linear TV. So that inflection point, where globally they're roughly equal at the moment, has already happened in Australia,” says Bisson.

“That's why it's such an interesting market. Outside of this market, the money has already followed. Here the money is staying with the broadcasters and the linear channels. It is much more resistant to the shift that we're seeing elsewhere,” he adds.

"Globally, if we put to one side the Netflixs and the Amazons who are new to the market, the money is shifting to online video – largely Google and Facebook. That [shift] has been much quicker than it has been here. Globally we saw an inflection point where that number overtook television, depending on region, three, four or five years ago. Whereas here, we're only just reaching that point.”

Bow wave incoming

One theory behind local broadcasters' ability to defend their turf – to a degree – against the incursion of Facebook and Google is that most marketers understand the difference between long-form, broadcast quality content on the main screen in the house, versus small screen, lower quality content environments.

Problem is that the big streaming platforms can now also deliver that main screen experience within their ad tiers – plus targeting.

The streamers have also maxed out on subscriber growth. “They're effectively saturated, there are no new customers to find”, per Bisson, at least in the under 40s demo in most major markets. Hence piling into advertising.

He thinks the collapse in subscriber growth – artificially accelerated during Covid – took the likes of Netflix by surprise. Two bad quarters was all it took for them to change their tune on advertising.

“It was a big shock and literally within weeks the announcement came that they were launching an ad tier,” says Bisson. “Since then, all the major global streaming platforms bar Apple have moved into advertising as well.”

Revenue pressure has flowed into content production, meaning cheaper shows – non-scripted content, reality and entertainment, “the bread and butter of traditional TV” – have become more attractive to streamers. Plus, those formats allow them to localise and seek out growth pockets. Ampere's analysis suggests streamers are still light on those genres in Australia and elsewhere, but are beginning to ramp up.

Likewise, the big platforms are starting to actively target older demos, TV’s heartland, which to date have proven less prone to switching wholesale to on demand delivery – and to paying.

Bisson says that shift is why Australian broadcasters are now suddenly under such pressure – as articulated consistently at the Future of TV Advertising conference earlier this month.

“The big difference now [versus social media’s incursion] is that the streamers, the Netflixs and Amazons of this world, have really good, high quality long-form programming that people tend to watch on their main big screen in the sitting room,” he says.

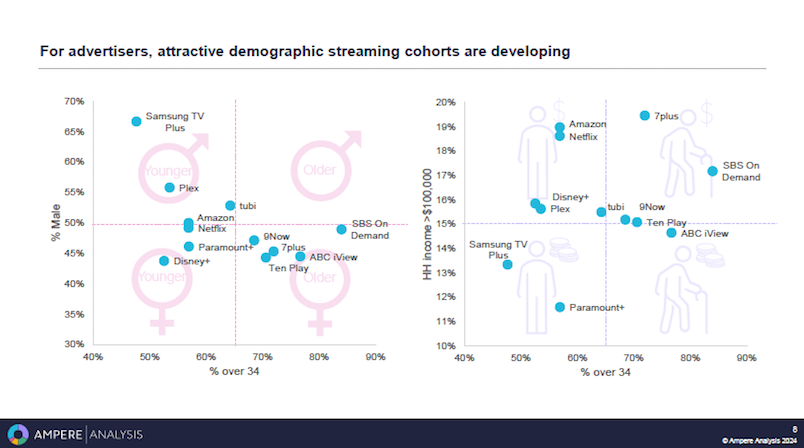

“It really is much closer to the broadcast viewing experience than perhaps social video, and the potential for it to begin to take market share, especially as it attracts a younger, wealthier audience, is quite significant … The additional option they bring is an ability to target … And in cases like Amazon they also know what you have been searching for to buy,” says Bisson.

“So they have this double-pronged ability to do what TV does well, which is brand safe advertising across a large audience … and then they can do quite specific targeting,” he adds.

Hence for advertisers, he says, "It's no longer about ‘should I do TV, or should I do online?’ It's, ‘I can do everything I can do on TV on streaming’,” suggests Bisson.

“That’s a really interesting dynamic – and that is why everything has shifted in just this last eight to twelve months.”

Broadcasters would argue they have just as much targeting capability as a Netflix, given they have logged-in users via their BVOD platforms. Plus arguably far greater advertising know-how, given they have been doing it for decades versus months, aligned to local market knowledge.

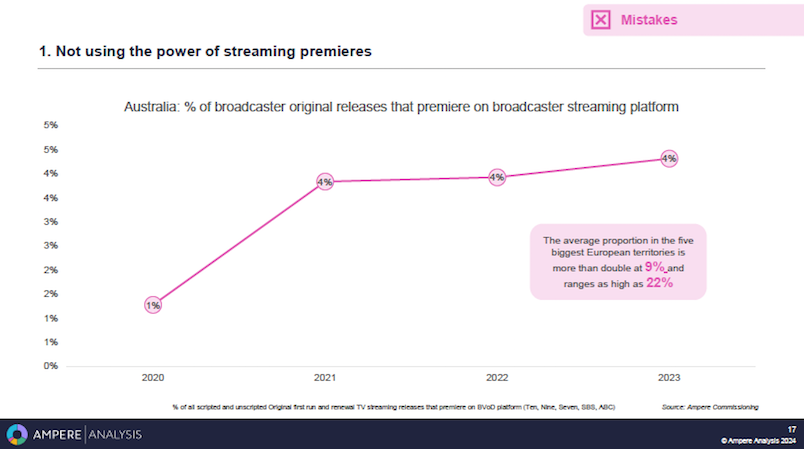

Bisson agrees broadcasters can compete on targeting, but says they need to go all-in on streaming first.

“Yes they can [leverage first party log-in data]. But that's why it's so important that they get that strategy around their streaming assets right. Because the data shows that they are still losing that young audience on those platforms. Whereas Netflix and Amazon are mopping up those younger, wealthier audiences,” he says.

“We don't mean the entire young audience has deserted broadcast, absolutely not. But they're starting to skew away from that audience. And that's why a digital-first strategy for the broadcasters – who, to some degree have rested on their laurels in this market, because television spend has not shifted to the degree it has elsewhere – becomes so important now with the entrance of [ad-funded] streamers.”

Streamers reprogramming

Bisson reiterates that Australian households are still watching a lot of broadcast linear TV – and the market consensus is that linear audience leakage has subsided so far this year.

“That is where they are going for a lot of their content … so it is still a really important medium – there are still many types of content that only really work when they're delivered live, for which linear TV is very effective,” he says.

“But it is changing and it is under threat – and if you're in business, you're seeking the strongest growth you can get for your shareholders and investors. Thus you need to address where the market is heading.”

He points out that the streamers are now targeting both older audiences – with “an influx” of crime and documentary programming as well as starting to woo younger audiences over the last 12 months with unscripted and reality shows.

“They're increasingly encroaching on the footprint of broadcasters’ base with unscripted and with stuff for older people. So content strategy becomes key to success.”

Broadcaster defence strategies

Bisson thinks TV networks could lift some of the streamers’ playbook to re-engage younger audiences while retaining the older demographics.

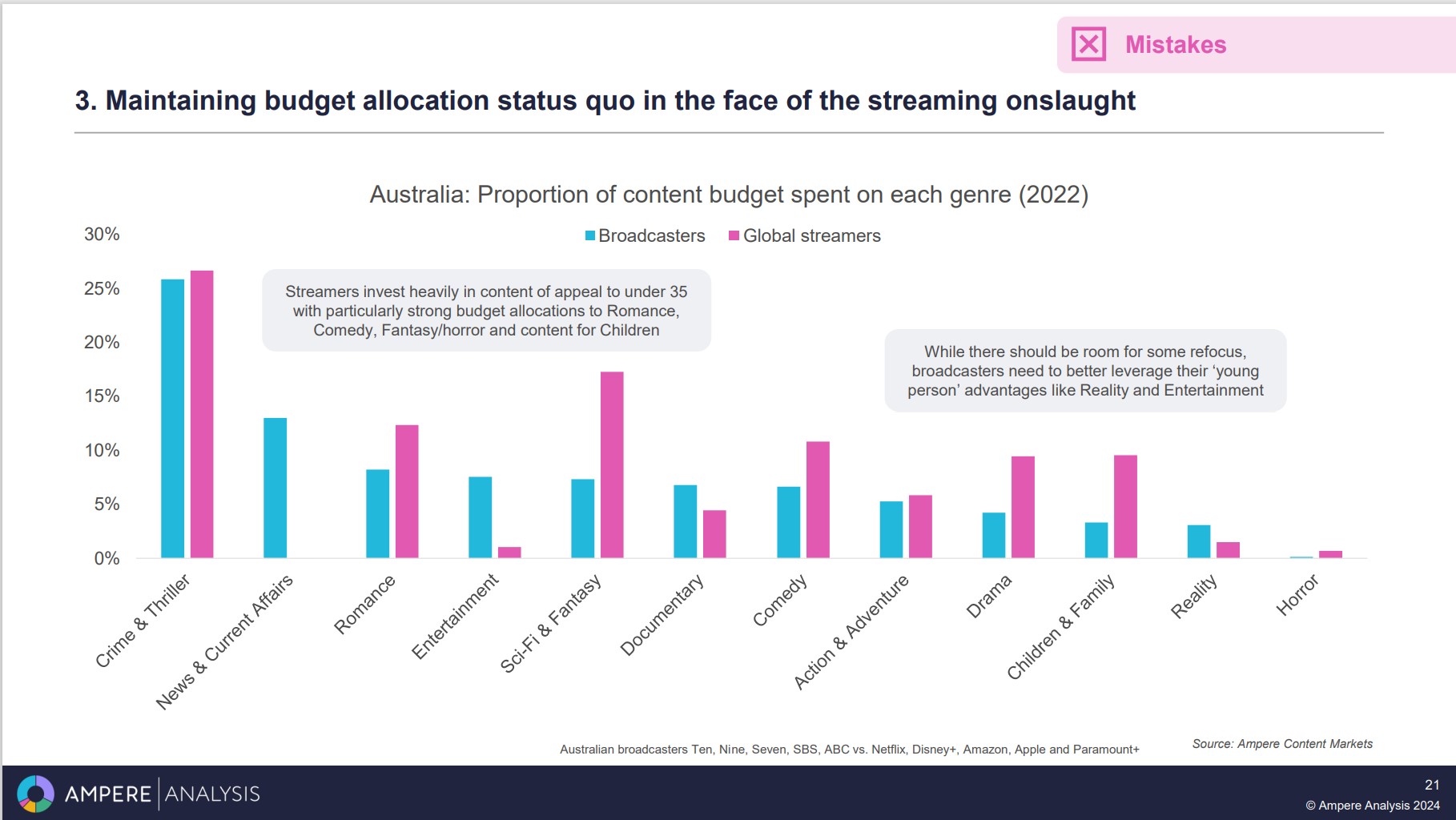

“There are certain genres young people really engage with … What we see consistently in the data is that comedy is number one. Obviously, content aimed at children and young families is strong for those younger households. And then we've got content like romantic drama that is also strong for younger age groups,” he says.

“So if you look at streamers’ [content] budget allocation, that's where a lot of the focus is. Whereas the broadcasters have other requirements … they spend a lot more on entertainment segments, because a lot of that content is still unscripted. And then they have commitments around news and current affairs programming that the streamers don't really have to worry about,” says Bisson.

“One of the things I argue is that, look at what the streamers do well and shamelessly copy it. If you can't copy literally – because you haven't got the budget, haven't got the volume of content – at least you can copy from a perception perspective.”

Ultimately, he says, premiering those shows on streaming platforms will bring back younger audiences that have cut the terrestrial broadcast cord. Currently, only 2 per cent of Australian broadcasters' reality shows premiere on their streaming platforms, per Ampere's analysis, and only 4 per cent of their broader slates take a streaming-first approach.

“Content like Love Island is very, very powerful for that demographic. It's how you prioritise that on the streaming side [as a] digital-first strategy [to] highlight that type of content, bring it to the forefront for that younger audience. It's also extremely good for longer-term engagement, because the series tend to run over many weeks. Whereas typically now for drama, the audience is used to a box set dropping on day one … and from an audience perspective that engagement over a longer term is really, really important,” he adds.

“We're not saying in any way that one should ignore drama or high budget content and just focus on reality TV and Love Island-type shows. But it's about how you position that, how you use it to premiere on the streaming platform, how you engage with ancillary content around those key shows for the younger audience on the streaming platform, without ignoring the power of those higher budget dramas.”

Sports rights next?

The big streamers are likewise bidding for sports rights – live free-to-air and pay TV’s crown jewel. Meanwhile, pure-plays like DAZN are aiming to become “the Netflix of sports … buying up rights globally for lower cost sport, but also crucially, buying some of that really premium sport”, says Bisson.

In the US that threat, along with spiralling rights costs, has led Walt Disney's ESPN, Fox Corp and Warner Bros. Discovery to put aside rivalries and create a combined sports streaming play, subject to clearing a Justice Department antitrust review.

Bisson points out that streamers haven’t always made a success of premium sports rights – with Amazon now pulling back after airing some Premier League games in the UK, “so it obviously didn’t work out that well for them”.

But he thinks streamers’ footprints could create an opportunity to take lower cost rights – i.e. Apple taking global rights for Major League Soccer, largely unwatched outside of the US – and “build it into something really big globally, thus creating value for both partners.”

There's an old forecasters adage: ‘We always overestimate the short-term and underestimate the long-term’. So yes, we're again in a period of intense change. But it's very easy to overestimate that in the short-term and then underestimate the longer-term. So it's about positioning for that medium and long-term change that is coming. There is still time ... but don't miss the boat.

“There's still time – and understanding it is key. But don't miss the boat

United front?

Could Australia’s broadcasters better withstand an ad-funded streaming assault by lifting ESPN, Fox Corp and Warner Bros. Discovery’s approach to co-operation?

“That's a very interesting question,” says Bisson. He thinks it could work both from a pooled resources perspective and an audience perspective, because sports audiences will otherwise have to pay for more subscription services if rights fragment across multiple platforms.

“Being able to go to one place to get all of the sport they want is a positive for the viewer base.”

Old is new

The upshot of current disruption, suggests Bisson, is that the market will end up returning to its old divide: pay TV versus free TV, however it is delivered. He thinks there is still significant appetite for the free version.

“The broadcasters are not going to die. Their strategies need to evolve, but they can continue to gain a significant share of the free-to-air market where they've traditionally been strong. As long as they continue to think about what the audience demands, and what sort of content is going to bring them on to streaming," says Bisson. "And as long as they start to think of these streaming platforms as a primary form of delivery, not a secondary form of delivery."

While broadcasters are facing into accelerated disruption, Bisson thinks some of the immediate impact locally may be overcooked.

“There's an old forecasters adage: ‘We always overestimate the short-term and underestimate the long-term’. So I would caution that yes, we're in a period of intense change again. But it's very easy to overestimate that in the short-term and then underestimate the longer-term. So it's about positioning for that slightly longer, medium and long-term change that is coming,” he says.

“There's still time – and understanding it is key. But don't miss the boat.”

There's always more in the podcast. Get the full download here.