Ex-Google, Uber marketer Laura Jones lifts brand building playbook to reverse slide at performance ‘obsessed’ Instacart – crushes it; James Hurman doubles down on Scott Galloway counteroffensive

An Mi3 editorial series brought to you by

QMS

L-R: WARC Content SVP David Tiltman, Tracksuit's James Hurman and Instacart CMO Laura Jones, who set about moving a management team “obsessing over channel-level ROAS [return on ad spend]” to see the bigger picture - and won.

An Mi3 editorial series brought to you by

QMS

Instacart CMO Laura Jones joined the $12.5bn delivery app just as the Covid boom fizzled and easy demand dried up. The tech platform had literally no brand budget and was all performance. So she went to work, reorganising teams, reshaping the brand and reading the effectiveness playbook, chapter by chapter, to the c-suite. They bought it – to the extent that they footed a Super Bowl ad this year that boosted sales 14 per cent and nearly doubled new visitors to the site. Jones, a former Google and Uber marketer, agrees with Previously Unavailable founder James Hurman that those suggesting brand is dead are way off the mark. Here’s what she did, and why Hurman thinks CEOs should stop listening to “big, confident voices” that are “completely incorrect” about the relationship between brand, advertising and hard financial growth.

What you need to know:

- Ex-Google and Uber marketer Laura Jones had to flip Instacart’s model when she landed in 2021. It was a performance maxi, zero brand budget.

- Problem was, nobody in the top ranks really believed in brand. They just wanted the short term ROAS at a channel level. So she did a trick: wrapping performance and brand together – in terms of investment and teams – and then just made it one overall “portfolio” returns approach.

- It worked – but only after it initially failed because they didn’t put enough media dollars behind the first big brand push.

- Now it’s powering – 14 per cent sales boost and new customers flooding in after a Super Bowl campaign.

- Jones says those still touting the old growth hacking playbook and Silicon Valley mindset that product and innovation alone will drive growth are sorely mistaken.

- Previously Unavailable founder James Hurman agrees – and repeats his warning not to listen to those who say otherwise, or risk disaster.

Tech companies universally – especially when they get to a certain stage – dawn on the realisation that product won’t do it alone. Once the latent demand has been tapped, once the lower funnel existing demand has been captured, there is no choice but to generate demand

Laura Jones spent a decade in Silicon Valley at Google and Uber before joining Instacart. So she knew what she was getting into.

But Jones flipped ‘move fast and break things’ to ‘move moderately and methodically fix things’ via old school marketing effectiveness rules, weaning management off a diet of pure performance marketing and channel-level ROAS (return on ad spend) metrics – and getting everybody pulling in the same direction.

There’s more to it than that. But within three years the $12.5bn grocery delivery platform went from having “zero” brand budget to a Super Bowl ad that Jones said lifted sales 14 per cent and poured a Nebuchadnezzar-load of new customers into the funnel, underlining the symbiotic relationship between brand and performance marketing.

Or as ad effectiveness expert, Tracksuit co-founder and Previously Unavailable boss James Hurman put it, proving the likes of Professor Scott Galloway “completely incorrect” when they say “the era of brand is dead”. (A point Hurman has made robustly and backed with plenty of data, here.)

Jones concurred. “Tech companies universally – especially when they get to a certain stage – dawn on the realisation that product won’t do it alone. Once the latent demand has been tapped, once the lower funnel existing demand has been captured, there is no choice but to generate demand, and more importantly, to make a meaningful connection with customers,” she told Cannes.

Hence the world’s top brands – tech companies – are among the world’s biggest spenders on advertising.

“In the end, no matter how great the product is, people are always going to copy you, it’s always going to be an arms race,” said Jones. “So what that means, whether it’s tech or any other industry, to really drive success, is [you need] to build that preference and make that lasting connection with the customer, so that next time they come to market, they come looking for you specifically.”

Which is a short version of what Jones told Instacart’s top brass. They bought it.

The first thing we did was to do away with the distinction between brand budget and performance budget. We just merged it and said ‘this is a portfolio budget to invest in full funnel’.”

Funnel flip, sales rip

The marketing funnel was actually invented by a salesman, per James Hurman. Hence some reliability issues.

“The AIDA framework [which posits that] if we attract attention and then interest, and then desire and then drive action, our advertising will cause people to go out and buy things … was created by a salesperson called Frank Dukesmith. It’s a great model to show how sales works, but not a very good model to show how advertising works,” he told Cannes.

The long and short of it is that most people are not in market for a given product at any one time, but sooner or later will be in market. Hence piling the lion’s share of budget into demand capture – i.e. performance marketing – is wasted money. It’s better to make sure people consider your brand when they are ready, investing in brand to be in mind at that point while also having the product in front of them, per Hurman, and pretty much every other effectiveness thinker.

But performance metrics capture hard results, whereas brand metrics are less clear cut, although the likes of Dr Grace Kite (founder of Magic Numbers, since acquired by Analytic Partners) suggest that ROAS is largely a factor of the level of demand within a category.

Either way, brand investment up front should make performance dollars deliver greater bang for buck: Hurman and Tracksuit have conducted studies with TikTok that show “if you are a brand with 60 per cent awareness, your conversion rate is about three times higher than if you are a brand with awareness of about 20 per cent.”

“So what does that tell us?” asked Hurman. “It tells us we need to create as much demand for our brand as possible, because that will push ROAS up as [buyers] come into the market … When we build future demand, we make an investment into the people that are going to come into the category later – and that investment pays off … The conversion rates are much higher and it’s an investment into the future success and efficiency of our performance marketing. But we need to measure these two things really differently.”

All of which Instacart’s Jones had to lay out for the exec team and a broader business hooked on demand harvesting over demand creation.

Lizzo, a fail, and a rethink

“When I got to Instacart, we were heavily concentrated in lower funnel marketing. We had no brand budget, no brand team, it was lower funnel all day long.”

Meanwhile, the pandemic ecom boom was fizzling out, demand fading. So Jones set about moving a management team “obsessing over channel-level ROAS [return on ad spend]” to see the bigger picture. That meant “educating the rest of the C-suite on the theory of brands … and going out with a business case that said ‘if we can invest not just in lower funnel but in upper funnel, we can maximise portfolio ROAS, and through that, we’ll be able to not just capture waning demand, but actually create demand in category.”

First she had to build a brand “worthy of investing in”. Which meant a total refresh and then, one year into the job, a campaign fronted by Lizzo.

But it didn’t work.

“The problem was it was wildly underpowered. We had very little brand budget. So we invested a tonne of love and money into this campaign, and it got very limited impressions. Meanwhile, we’re spending performance marketing dollars all day long,” said Jones. Plus, the two teams were hell bent on staying in their own swim lanes.

“I realised we had to change everything about the way we’re working,” said Jones. “The first thing we did was to do away with the distinction between brand budget and performance budget. We just merged it and said ‘this is a portfolio budget to invest in full funnel’.”

A great artist steals

The upshot was a more integrated approach between performance, brand and their outputs. It took a while to work, Jones acknowledged, “but over time we came to be able to prove that when we have more emotive storytelling supported by lower funnel assets, it actually moved the needle for our top line growth.”

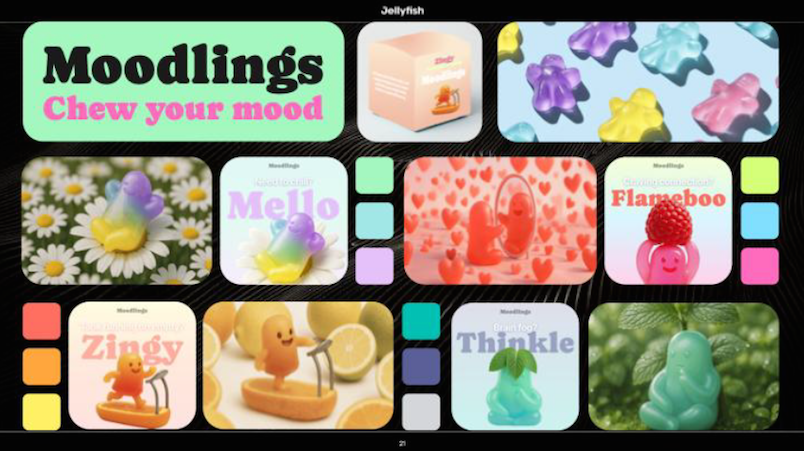

Which culminated in the business signing off on a big, expensive Super Bowl ad that literally lifted all the brand characters and mascots of a who’s who of CPG advertising.

The TV ad was linked to mascots “roaming New York City” to social teasers and to “app incentives to help convert that traffic”, said Jones. “It worked incredibly well. We increased new to site visitors by 72 per cent after the Super Bowl and increased sales 14 per cent. It was a huge win – and it really paid off this promise of full funnel marketing on the biggest stage possible.”

Perhaps more importantly, the Super Bowl ad and its hard growth impacts “provided this incredible rallying moment” where all those previous swim-lane purists “could see what is felt like when we were all rowing in the same direction,” per Jones.

Which meant everybody bought in to doing more of the same – via a system Jones called “create your own weather” intended to overcome what she terms “limiting beliefs”.

“A limiting belief is a story you tell yourself about what is possible, or rather what is not possible, that keeps you from being able to achieve a goal.” Jones cited performance marketers not believing brand is going to hit their quarterly target, likewise brand marketers and creatives fearing the performance crew “is going to water down our idea, kill its soul and it’s going to end up really lame”. Meanwhile those responsible for product and revenue are wondering “how do we get product in there?”

The first outward execution of the ‘create your own weather’ system is a discounting campaign that, while powering acquisition and volume, also builds brand: “It’s called ‘Summer like it’s 1999’” said Jones, with the brand tapping a wave of nostalgia for simpler times – microwave pizza, Capri-Sun – and easing a wallet squeeze as inflation, tariffs and geopolitech uncertainties bite.

Pulling the price lever – with brands discounting to 1999 prices, on average, 47.2 per cent cheaper – is working for all sides of the marketplace, per Jones: “They have been selling like hotcakes.”

But the discounting and hot sales performance button ladders back to the brand, said Jones, meaning Instacart is triggering immediate demand, scooping it up, and adding fuel to the future fire: “This feels like the beginning of ‘create your own weather’ full funnel marketing for us.”

Brand is dead… long live brand

Warc chief content officer David Tiltman outlined key blockers to rebalancing brand and demand investment, the most “insidious” of which, he suggested, is “a CEO who thinks brand is irrelevant”.

Tiltman dubbed Professor Scott Galloway “the high priest of this particular point of view … [stating repeatedly that] ‘the era of brand is dead’ and this idea that it’s now all about tech, innovation and supply chain magic and that brand doesn’t really drive shareholder returns in the way that it used to. Which is a tricky [perception] to shift, because people like Scott have the ear of the CEO,” per Tiltman.

(Galloway has stated that: “What the companies that have added over $100 billion in value in the last decade have in common is they don't advertise … I think advertising outs you as not getting it,” and variations of that theme.)

New York University Professor Scott Galloway

Tiltman duly handed over to James Hurman to counter Galloway’s point of view. Hurman reiterated this clinical rebuttal: In short, the big firms adding billions of dollars in shareholder value and outperforming the market are all major advertisers, and Professor Galloway may be guilty of projecting his own habits and preferences onto the broader market.

(“If advertising ‘outs you as not getting it’, then Apple, Google, Tiktok, Nvidia, OpenAI don't get it. Which makes me wonder, who does get? Maybe it's Amazon, the world's biggest advertiser,” per Hurman).

“What fucks me off is that when the CEOs and boards of the world listen to the big, confident voice of Professor Galloway and they hear him say ‘you don’t need to advertise, you don’t need to build brand’, what does that mean for us? If the ad budget gets zeroed and the marketing team gets reduced, it’s not good for us and it is terrible for the businesses that we serve,” said Hurman.

“So I think it’s important for us that we do stand up for ourselves, do stand up for our discipline and we do point out that this very American tradition of saying things very loudly and very confidently, is not something that we want to accept.”

Which raised a cheer on the French riviera.